Preface

When learning other programming languages, such as Java, I know that the amount of code required to complete a good robust program is likely to be three times amount of function code.

The programs we write must withstand the test of various anomalies and errors, and try to keep the system from crashing even under the worst conditions.

In First meet with Erlang, we already know Robustness is important feature of Erlang, so this learning, let’s understand how Erlang keep good robustness.

Text

Recall the Ping-Pong example in earlier Blog Erlang learning (7) - Concurrent Programming (3), what will happen if something wrong?

Such as, if a node where a user is logged on goes down without doing a logoff, the user remains in the server’s User_List, but the client disappears. This makes it impossible for the user to log on again as the server thinks the user already is logged on.

Or if the server goes down in the middle of sending a message, leaving the sending client hanging forever in the await_result function?

To avoid this waiting forever, we can use time-outs mechanism.

Time-outs

Take Ping-Pong example for earier understanding of time-outs:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

-module(tut14).

-export([start_ping/1, start_pong/0, ping/2, pong/0]).

ping(0, Pong_Node) ->

io:format("ping finished~n", []);

ping(N, Pong_Node) ->

{pong, Pong_Node} ! {ping, self()},

receive

pong ->

io:format("Ping received pong~n", [])

end,

ping(N - 1, Pong_Node).

pong() ->

receive

{ping, Ping_PID} ->

io:format("Pong received ping~n", []),

Ping_PID ! pong,

pong()

after 5000 ->

io:format("Pong timed out~n", [])

end.

start_pong() ->

register(pong, spawn(tut14, pong, [])).

start_ping(Pong_Node) ->

spawn(tut14, ping, [3, Pong_Node]).

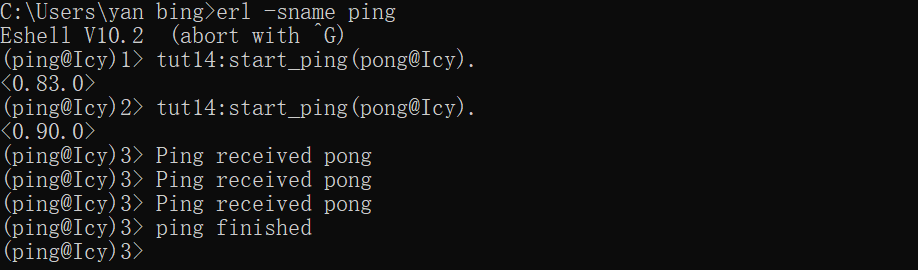

Test:

The time-out (after 5000) is started when receive is entered. The time-out is canceled if {ping,Ping_PID} is received. If {ping,Ping_PID} is not received, the actions following the time-out are done after 5000 milliseconds. after must be last in the receive, that is, preceded by all other message reception specifications in the receive. It is also possible to call a function that returned an integer for the time-out:

1

after pong_timeout() ->

In general, there are better ways than using time-outs to supervise parts of a distributed Erlang system. Time-outs are usually appropriate to supervise external events, for example, if you have expected a message from some external system within a specified time. For example, a time-out can be used to log a user out of the messenger system if they have not accessed it for, say, ten minutes.

Learning notes: why do not add time-outs for ping process? If process pong dead, ping will wait forever? So do below test:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

-module(tut15).

-export([start_ping/1, start_pong/0, ping/2, pong/0]).

ping(0, Pong_Node) ->

io:format("ping finished~n", []);

ping(N, Pong_Node) ->

{pong, Pong_Node} ! {ping, self()},

receive

pong ->

io:format("Ping received pong~n", [])

end,

ping(N - 1, Pong_Node).

pong() ->

receive

{ping, Ping_PID} ->

io:format("Pong received ping~n", []),

Ping_PID ! pong,

exit(normal) % do not call pong(), receive once and exit.

end.

start_pong() ->

register(pong, spawn(tut15, pong, [])).

start_ping(Pong_Node) ->

register(ping, spawn(tut15, ping, [3, Pong_Node])). %register ping, try to use whereis(ping) to check if process ping alive

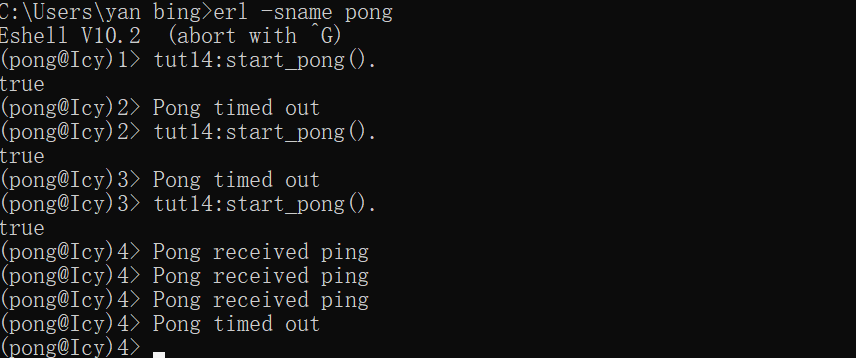

Test:

Learning notes: both process ping and pong need time-outs. The only reason for first example wihtout ping timeout, because pong process is created firsly, if process ping is not created, pong will wait forever. But besides this error condition, we need also consider possibility that process dead during conmunication.

Error Handling

Knowledge points:

- exit/1:

A process which executes exit(normal) or simply runs out of things to do has a normal exit.

A process which encounters a runtime error (for example, divide by zero, bad match, trying to call a function that does not exist and so on) exits with an error, that is, has an abnormal exit. A process which executes exit(Reason) where Reason is any Erlang term except the atom normal, also has an abnormal exit. - link/1:

An Erlang process can set up links to other Erlang processes. If a process calls link(Other_Pid) it sets up a bidirectional link between itself and the process called Other_Pid. When a process terminates, it sends something called a signal to all the processes it has links to.

The signal carries information about the pid it was sent from and the exit reason.

The default behaviour of a process that receives a normal exit is to ignore the signal. - abnormal exit:

The default behaviour in the two other cases (that is, abnormal exit) above is to:

- Bypass all messages to the receiving process.

- Kill the receiving process.

- Propagate the same error signal to the links of the killed process.

- spawn_link:

With the default behaviour of abnormal exit and link mechanism, we can connect all processes in a transaction together using links. If one of the processes exits abnormally, all the processes in the transaction are killed.

As it is often wanted to create a process and link to it at the same time, there is a special BIF, spawn_link that does the same as spawn, but also creates a link to the spawned process.

Ping-Pong Example

Take Ping-Pong example to use link to terminate process “pong”:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

-module(tut16).

-export([start/1, ping/2, pong/0]).

ping(N, Pong_Pid) ->

link(Pong_Pid),

ping1(N, Pong_Pid).

ping1(0, _) ->

exit(ping);

ping1(N, Pong_Pid) ->

Pong_Pid ! {ping, self()},

receive

pong ->

io:format("Ping received pong~n", [])

end,

ping1(N - 1, Pong_Pid).

pong() ->

receive

{ping, Ping_PID} ->

io:format("Pong received ping~n", []),

Ping_PID ! pong,

pong()

end.

start(Ping_Node) ->

Pong_PID = spawn(tut16, pong, []),

spawn(Ping_Node, tut16, ping, [3, Pong_PID]).

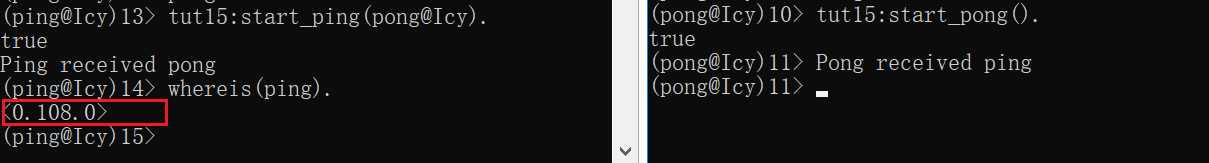

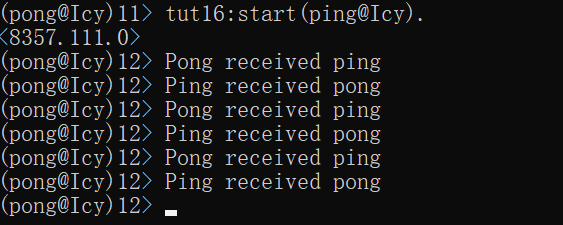

Test:

Learning notes: I understand that all the output is received on Erlang node (pong@Icy). This is because the I/O system finds out where the process is spawned from and sends all output there.

This is a slight modification of the ping pong program where both processes are spawned from the same start/1 function, and the “ping” process can be spawned on a separate node. Notice the use of the link BIF. “Ping” calls exit(ping) when it finishes and this causes an exit signal to be sent to “pong”, which also terminates.

It is possible to modify the default behaviour of a process so that it does not get killed when it receives abnormal exit signals. Instead, all signals are turned into normal messages on the format {‘EXIT’,FromPID,Reason} and added to the end of the receiving process’ message queue. This behaviour is set by:

1

process_flag(trap_exit, true)

There are several other process flags. Changing the default behaviour of a process in this way is usually not done in standard user programs, but is left to the supervisory programs in OTP. However, the ping pong program is modified to illustrate exit trapping.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

-module(tut17).

-export([start/1, ping/2, pong/0]).

ping(N, Pong_Pid) ->

link(Pong_Pid),

ping1(N, Pong_Pid).

ping1(0, _) ->

exit(ping);

ping1(N, Pong_Pid) ->

Pong_Pid ! {ping, self()},

receive

pong ->

io:format("Ping received pong~n", [])

end,

ping1(N - 1, Pong_Pid).

pong() ->

process_flag(trap_exit, true), % modify the default behaviour of a process so that it does not get killed when it receives %abnormal exit signals.

pong1().

pong1() ->

receive

{ping, Ping_PID} ->

io:format("Pong received ping~n", []),

Ping_PID ! pong,

pong1();

{'EXIT', From, Reason} -> % abnormal exit signals are turned into normal messages on the format {'EXIT',FromPID,Reason} %and added to the end of the receiving process' message queue.

io:format("pong exiting, got ~p~n", [{'EXIT', From, Reason}])

end.

start(Ping_Node) ->

PongPID = spawn(tut17, pong, []),

spawn(Ping_Node, tut17, ping, [3, PongPID]).

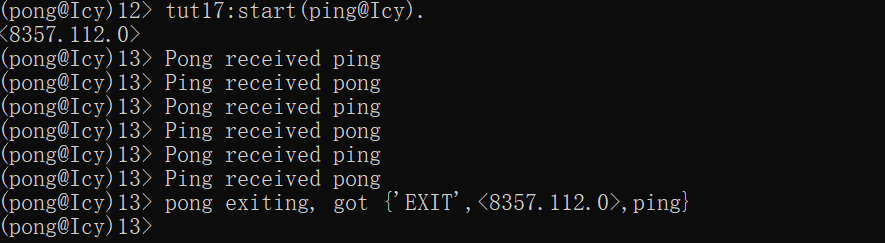

Test:

Summary

This study is mainly to understand some of the implementation of the robustness of the Erlang program. But compared to the mechanism of exception handling such as Java, these Erlang exception handling mechanisms learned today should be just the beginning.

Reference

http://www.erlang.org

http://erlang.org/doc/getting_started/robustness.html