Preface

One of the main reasons for using Erlang instead of other functional languages is Erlang’s ability to handle concurrency and distributed programming. By concurrency is meant programs that can handle several threads of execution at the same time.For example, modern operating systems allow you to use a word processor, a spreadsheet, a mail client, and a print job all running at the same time.

Let’s see how Erlang realize concurrency and distributed programming.

Text

Processes

What’s process

Each processor (CPU) in the system is probably only handling one thread (or job) at a time, but it swaps between the jobs at such a rate that it gives the illusion of running them all at the same time. It is easy to create parallel threads of execution in an Erlang program and to allow these threads to communicate with each other. In Erlang, each thread of execution is called a process.

The term “process” is usually used when the threads of execution share no data with each other and the term “thread” when they share data in some way. Threads of execution in Erlang share no data, that is why they are called processes.

Learning notes: the concept of thread and process are consistent with those in Java.

In Java, each process has its own heap space, but threads of same process share the same heap spaces, but each thread has own stack space.

How to create process

The Erlang BIF spawn is used to create a new process: spawn(Module, Exported_Function, List of Arguments).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

-module(tut9).

-export([start/0, say_something/2]).

say_something(What, 0) ->

done;

say_something(What, Times) ->

io:format("~p~n", [What]),

say_something(What, Times - 1).

start() ->

spawn(tut9, say_something, [hello, 3]),

spawn(tut9, say_something, [goodbye, 3]).

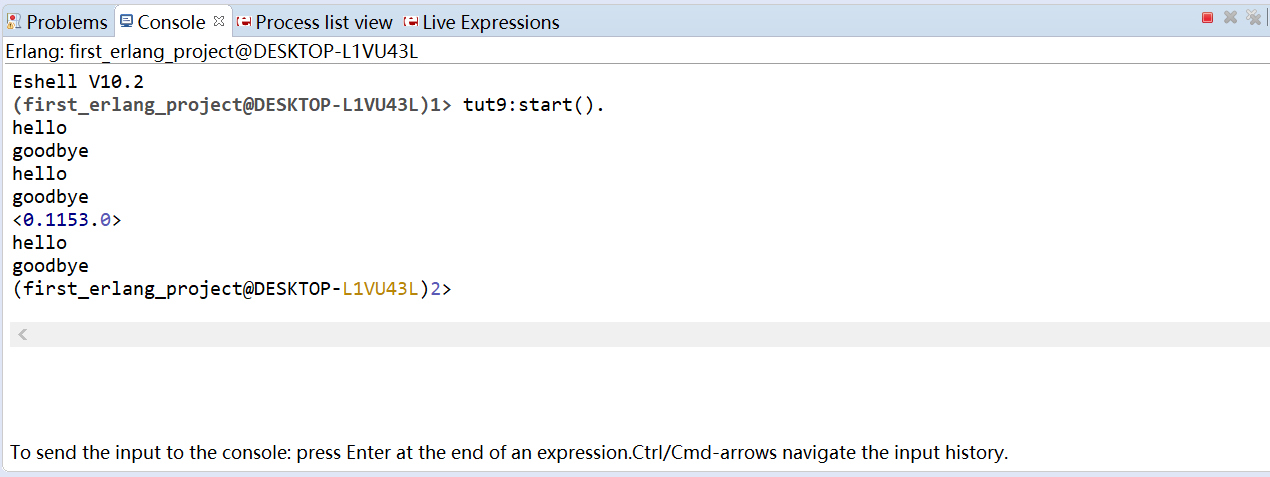

Test:

Knowledge Points:

- -export:

A function used in this way by spawn, to start a process, must be exported from the module. That is, in the -export at the start of the module. This should be noticed, because according to earlier study, it seems only start/0 should be exported, and say_something/2 seems like local function.

- output order:

Notice that it did not write “hello” three times and then “goodbye” three times. Instead, the first process wrote a “hello”, the second a “goodbye”, the first another “hello” and so forth.

Learning notes: I want to know, if the output alway has this order? How Erlang handle the process? Polling? Resource competition? To see if I can find answer later.

- process identifier:

where did the <0.1153.0> come from? The return value of a function is the return value of the last “thing” in the function. The last thing in the function start is spawn(tut14, say_something, [goodbye, 3]).

spawn returns a process identifier, or pid, which uniquely identifies the process. So <0.1153.0> is the pid of the spawn function call above.

Message Passing

Since processes do not share data each other, Erlang have to provide other way to let process communicate. They communicate by message passing. Let’s see the grammar used in passing messages firstly.

- The receive construct is used to allow processes to wait for messages from other processes. It has the following format:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

receive

pattern1 ->

actions1;

pattern2 ->

actions2;

....

patternN

actionsN

end.

Messages between Erlang processes are simply valid Erlang terms. That is, they can be lists, tuples, integers, atoms, pids, and so on.

Each process has its own input queue for messages it receives. New messages received are put at the end of the queue. When a process executes a receive, the first message in the queue is matched against the first pattern in the receive. If this matches, the message is removed from the queue and the actions corresponding to the pattern are executed.

However, if the first pattern does not match, the second pattern is tested. If this matches, the message is removed from the queue and the actions corresponding to the second pattern are executed. If the second pattern does not match, the third is tried and so on until there are no more patterns to test. If there are no more patterns to test, the first message is kept in the queue and the second message is tried instead. If this matches any pattern, the appropriate actions are executed and the second message is removed from the queue (keeping the first message and any other messages in the queue). If the second message does not match, the third message is tried, and so on, until the end of the queue is reached. If the end of the queue is reached, the process blocks (stops execution) and waits until a new message is received and this procedure is repeated.

The Erlang implementation is “clever” and minimizes the number of times each message is tested against the patterns in each receive.

Learning notes: what will happen to these messages are not matched in the queue? Is there still an opportunity to rematch these messages, such as matching condition changed? What is the significance of keeping these match failure messages?

- The operator “!” is used to send messages. Message (any Erlang term) is sent to the process with identity Pid.

The syntax of “!” is:

1

Pid ! Message

Ping-Pong Example

Two processes are created and send messages to each other:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

-module(tut10).

-export([start/0, ping/2, pong/0]).

ping(0, Pong_PID) ->

Pong_PID ! finished,

io:format("ping finished~n", []);

ping(N, Pong_PID) ->

Pong_PID ! {ping, self()},

receive

pong ->

io:format("Ping received pong~n", [])

end,

ping(N - 1, Pong_PID).

pong() ->

receive

finished ->

io:format("Pong finished~n", []);

{ping, Ping_PID} ->

io:format("Pong received ping~n", []),

Ping_PID ! pong,

pong()

end.

start() ->

Pong_PID = spawn(tut10, pong, []),

spawn(tut10, ping, [3, Pong_PID]).

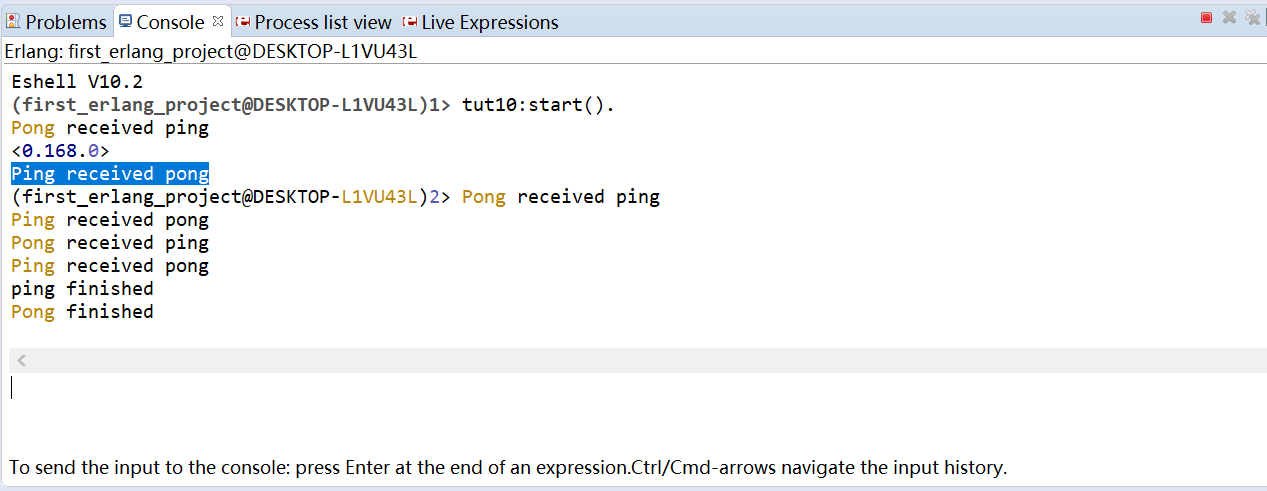

Test:

Program interpretation:

- <0.168.0>:

Return value of start/0 function. Pid of process Ping.

- self():

self() returns the pid of the process that executes self(). In this example, it’s the pid of “ping”.

Pid of “ping” lands up in the variable Ping_PID in receive code of “pong”.

Execution Logic:

- Function start first creates a process “pong”, Pong_PID is pid of “pong”, and wait for messages.

- Function start second creates a process “ping”, set communication time and Pong_PID.

- Communication time is 3, not 0, matching ping(N, Pong_PID) clause.

Send atom “ping” and pid of “ping” as message to “pong” process. And wait for new message. - Process “pong” find there is new message in input queue, message cannot match atom “finished”, then try match {ping, Ping_PID}.

New message match {ping, xx}, and set received xx value as variable Ping_PID.

Output and send atom “pong” to process “ping”. Recursive call pong() realize continuous receive. - process “ping” find there is new message in input queue, match atom “pong”, output and recursive call ping() with communication time-1 = 2, repeat step-3 to step-5, until communication time=0, to step-6.

- Process “ping” match ping(0, Pong_PID) clause, send atom “finished” to process “pong”, and output “ping finished”.

- Process “pong” find there is new message in input queue, message match atom “finished”, output “Pong finished”.

Summary

These methods used in concurrent programming have been touched in my previous blog First meet with Erlang, and this time I learn the processing logic and precautions in more detail.

For some of the questions in the study, I haven’t gotten the answer yet. I will continue to learn the rest of the knowledge of concurrent programming, hoping to find or think about the answer.

Reference

http://www.erlang.org

http://erlang.org/doc/getting_started/conc_prog.html

-

Previous

Erlang learning (4) - Sequential Programming -

Next

Erlang learning (6) - Concurrent Programming (2)